Review: Adieu (The National Ballet of Canada)

Adieu, the National Ballet of Canada’s latest program, is more than a performance—it’s a farewell to one of the country’s defining dance artists. After 26 years, Guillaume Côté takes his final bow as a principal dancer and one of the company’s first-ever Choreographic Associates. This run closes a chapter marked by passion, virtuosity, and a deep commitment to the Canadian dance sector.

There hasn’t been a male dancer at the National Ballet of Canada to match Côté since his rise. In his early years, he was the ultimate powerhouse—his jumps, turns, and technical precision were unforgettable. Like Karen Kain before him, Côté could have danced anywhere in the world. Instead, he chose to stay—shaping his career in Canada, founding his own company, Côté Danse, and now serving as Artistic Director of the Festival des Arts de Saint-Sauveur. This speaks to his belief in building something lasting within the national scene. His departure from the stage doesn’t mark an end so much as a shift in his contributions.

I have absolutely adored following Côté throughout his dance career, starting from when I was just a high school dance student. Côté has been at the center of Canadian ballet for my entire adult life. He remains an iconic figure in ballet across the world. His exit from the stage isn’t a surprise—he’s danced less with the company in recent years, shifting toward choreography and independent work—but it still lands with weight for balletomanes.

This farewell program unfolds in four parts: Bolero, Reverence, King’s Fall, and Grand Mirage. It opens with Bolero, an earlier work by Côté, and continues with two world premieres by Canadian choreographers—Ethan Colangelo’s Reverence and Jennifer Archibald’s King’s Fall, demonstrating the company’s continued investment in showcasing homegrown voices. The evening culminates with Grand Mirage, a newly commissioned multimedia piece choreographed by Côté himself, marking his final performance as a dancer with the company.

Côté’s Bolero is a thrilling work set to Maurice Ravel’s iconic score of the same name. Originally created for the National Ballet’s 60th Anniversary Diamond Gala in 2012, it’s a piece that deserves to be seen more often. Featuring one female dancer, Geneviève Penn Nabity, and four male partners—Christopher Gerty, Ben Rudisin, Peng-Fei Jiang, and Shaakir Muhammad—this piece explores the physical possibilities of a single, highly capable body supported and guided by four others. The movement slowly builds in intensity, as the men manipulate, lift, and roll Nabity through sweeping circular pathways and full-body rotations.

One of the most memorable moments comes in the form of a massive, assisted grand plié that moves in a wide descent to the floor. There’s a beautiful sense of escalation throughout, both in choreography and score. The lifts grow increasingly complex and daring throughout the work, some so intense that I physically flinched.

The minimalist costume design by Yannick Larivée and lighting by Jeff Logue complement the work perfectly, letting the physicality and structure take center stage. Given its impact, I’m genuinely surprised Bolero hasn’t appeared more frequently in the company’s repertoire—perhaps due to the inherent risk and technical demand of the partnering work.

After a brief pause, the program continues with Reverence by Canadian choreographer Ethan Colangelo. Inspired by Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights, the work investigates how opposing emotional states, like anxiety and euphoria, can coexist within the body. The choreography moves between smooth, connected waves and jerky, gesture-based movements that jolt and contract. The first half features a larger ensemble, while the second shifts toward duets and trios of partner work dispersed across the stage, creating a sense of fragmentation and intimacy.

There’s a moody, immersive atmosphere to the piece, aided by a fog-filled stage and an original score by Ben Waters that stands out for its otherworldly, layered textures. Jeff Logue’s lighting design adds to this effect, creating a dim, dreamlike space while maintaining crisp focus on the dancers. The overall tone of the piece is intriguing, but I found myself wishing for more development in the second half—a clearer arc or a more impactful conclusion to match the strength of the opening.

Following a twenty-minute intermission, the program resumes with King’s Fall, a chess-inspired work by Toronto choreographer Jennifer Archibald. Drawing on themes of strategy and sacrifice, the piece offers a commanding presence from start to finish. The choreography is sharp and tightly constructed, with a particular focus on strength, control, and precision. Pointe work plays a central role and is used to great effect, enhancing the intensity and edge of the movement vocabulary. Visually and rhythmically, the piece remains compelling throughout. My only critique lies in the way King’s Fall is billed as a hip-hop fusion. This feels like a stretch. I didn’t see any clear hip-hop elements within the movement itself. Nor does the work require this framing.

Last but not least, the most anticipated piece of the evening: Grand Mirage. A multimedia work choreographed by Côté in collaboration with Canadian filmmaker Ben Shirinian, the piece begins with a surreal, slightly eerie film sequence featuring Côté wandering through an old motel. The hotel becomes a symbolic space, one that reflects on the past while confronting an unknown future.

The stage opens into the motel room itself: cinematic in its detail, complete with a bed and a flickering vintage TV that Côté bangs in frustration, trying to make it work. The piece feels almost like a therapy session: intimate, reflective, and deeply personal. Understandably so—this is a major moment in his career. Throughout, Grand Mirage references key roles and moments from Côté’s past, almost like a pared-down, 35-minute Nijinsky. The pacing is slow, but I welcomed it. I was soaking up every moment of this familiar body onstage, one shaped by decades of knowledge and experience.

The final section features Peter Gabriel’s cover of “My Body Is a Cage,” with the repeated lyric “set my body free”—a fitting, almost painfully honest choice. The song reflects not just a farewell, but the vulnerability of a dancer coming to terms with a body that no longer moves as it once did. There’s no pretense here: Côté doesn’t try to recreate his younger self. Instead, he shares something far more generous, his self-awareness, his anxiety, and the quiet grief of transition. Grand Mirage isn’t a showcase of technical peak, but of emotional transparency. It offers a kind of truth that few dancers allow themselves to reveal.

It is emotional to watch Côté take his final bow as a principal dancer for the National Ballet of Canada. While I know he isn’t going far, this does feel like the end of an era. Thank you, Côté, for sharing your life and career. Much love.

Adieu, presented by the National Ballet of Canada at the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts (145 Queen St W, Toronto, ON M5H 4G1) is playing until June 5, 2025. For tickets, please click here.

National.Ballet.ca | Socials: @nationalballet

Photo credits:

- Photo 1: Guillaume Côté in Grand Mirage. Photo by Bruce Zinger.

- Photo 2: Artists of The Ballet in Bolero. Photo by Karolina Kuras.

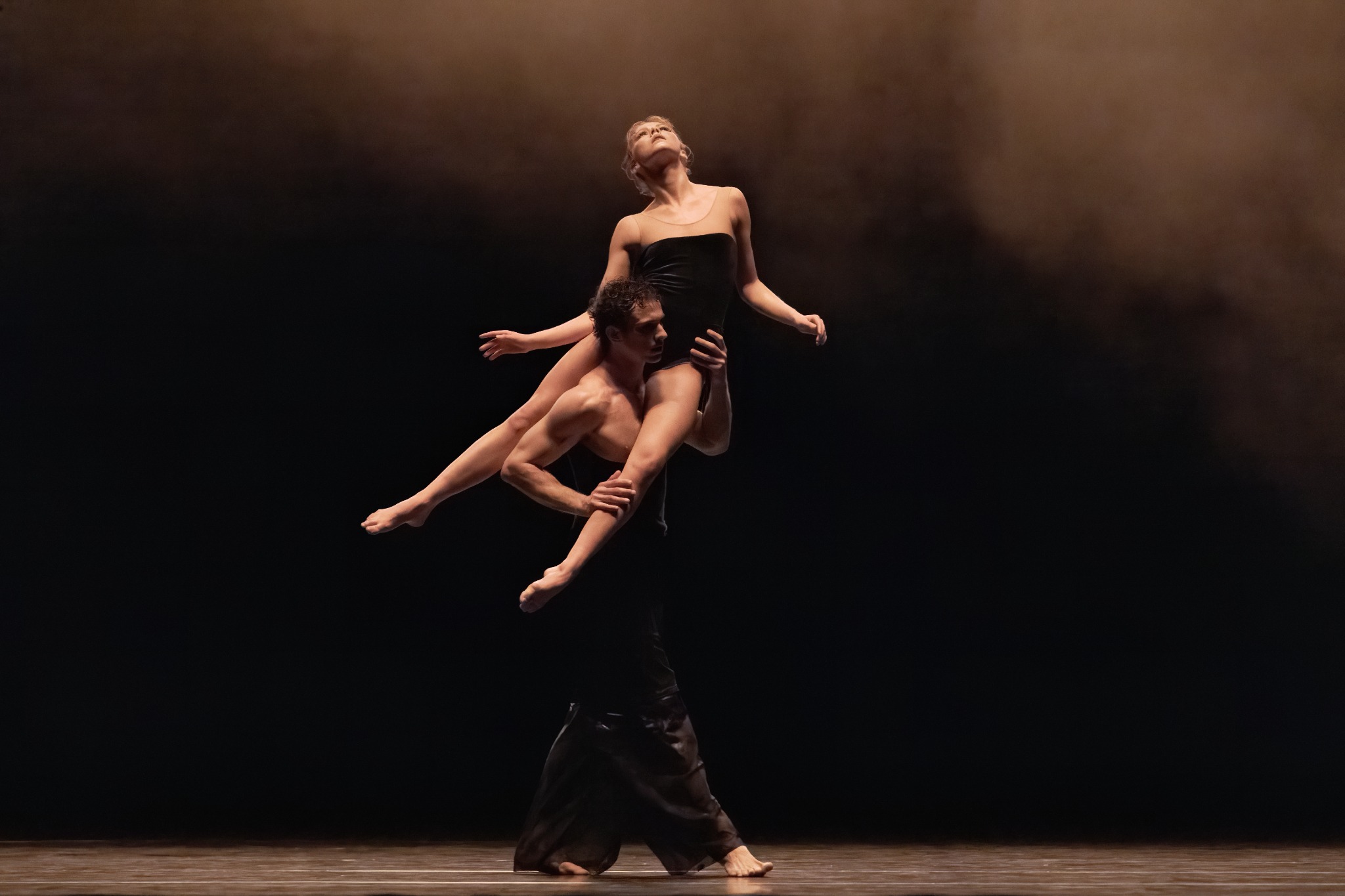

- Photo 3: Christopher Gerty and Isabella Kinch in Reverence. Photo by Karolina Kuras.

- Photo 4: Artists of The Ballet in King's Fall. Photo by Karolina Kuras.

- Photo 5: Guillaume Côté and Greta Hodgkinson in Grand Mirage. Photo by Karolina Kuras.

Written by Deanne Kearney | DeanneKearney.com @deannekearney

0 Comments Add a Comment?