Review: Sweet Ephemera (DanceWorks, Choreography by Calder White and Tavia Christina)

With a queer double bill timed to the end of Pride Month in Toronto, DanceWorks presents Sweet Ephemera, featuring two works by emerging choreographers Calder White and Tavia Christina. While queer artists deserve support year-round, there’s still something especially meaningful about a queer double bill landing at the tail end of Pride Month. These two works aren’t feel-good dances or mainstream crowd-pleasers. Both pieces, curated and produced by Dedra McDermott, embrace experimental forms to explore intimacy, absence, connection, and desire, leaning into the complexity and discomfort of queer life in ways that feel far removed from the city’s usual rainbow spectacle.

Tucked into the Studio Theatre at Young People’s Theatre, Sweet Ephemera felt right at home. It was my first time in the space, and I was pleasantly surprised by its intimacy and potential; a great venue find, especially as we continue to feel the absence of the Fleck Theatre (though there are whispers of its possible return). The evening was hosted by Brayden Jamil Cairns, who brought warmth, presence, and style in a stunning pink suit—a fantastic choice, and someone I would love to see host more events like this.

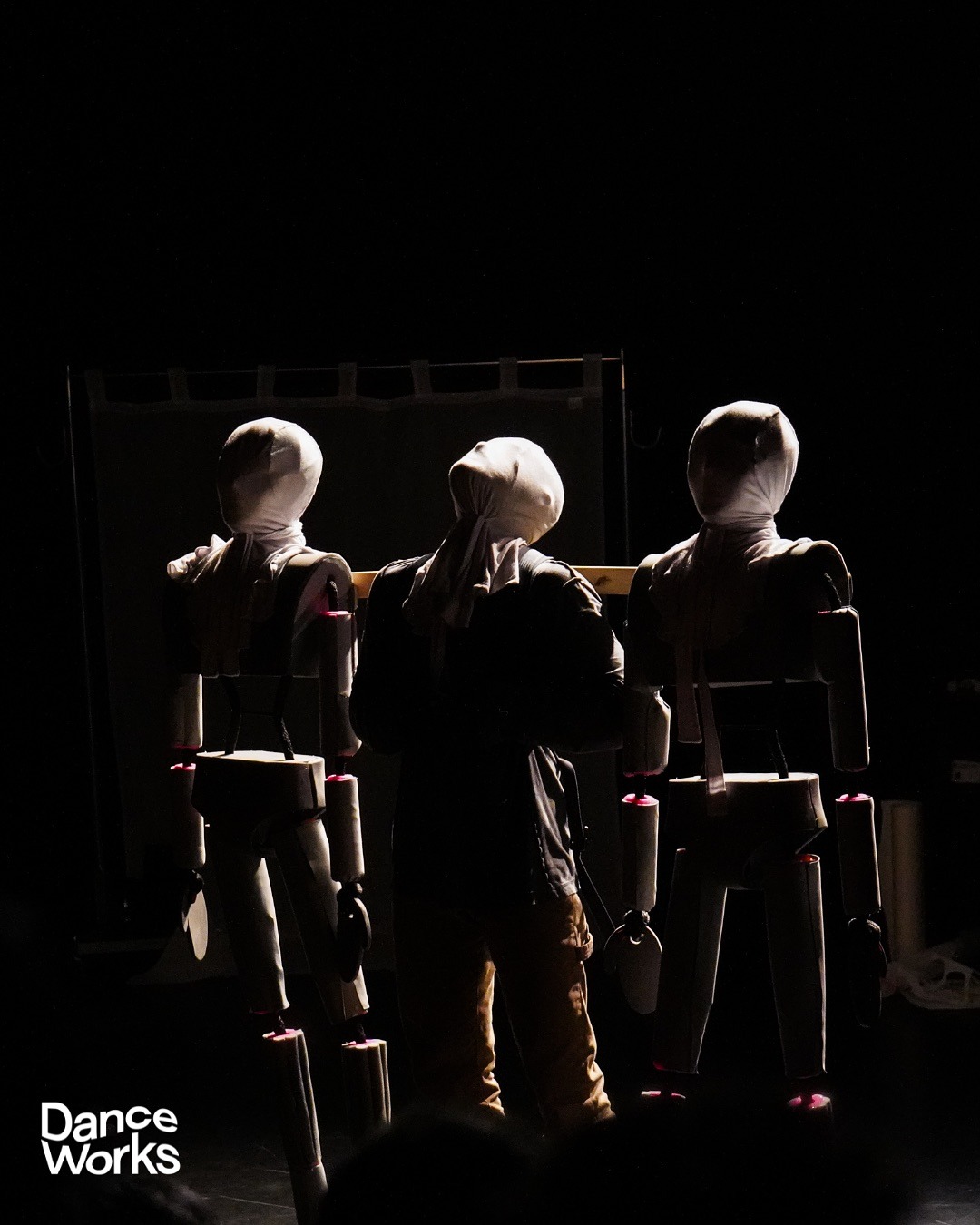

The night opens with only child, choreographed and performed by Calder White. The program describes it as “a solo that’s at times a duet and occasionally a trio,” which immediately intrigued me, especially with only one performer listed. I have always been drawn to unconventional duets (with shadow, video, or objects), and this piece builds gradually toward that promise.

White begins the work alone onstage, accompanied only by a grey, humanoid figure whose limbs are made from pool noodles. Its face is covered by a white mask identical to his own. At first, it’s simply present, not yet a partner. A second figure, hidden behind a stark white curtain, is later revealed through lighting as White dresses it like himself. As the piece progresses, these figures shift from objects in space to partners in motion: one shares an intimate hug and slow dance with White; later, both are bolted to a wooden plank, with White in the middle, controlling their movements in a haunting trio. Their lightness means they respond to White’s smallest movements, even his breath, creating uncanny movements.

According to the program notes, only child examines “courtship, reproduction, and romance on a pedestal and under a microscope,” drawing from queer intimacy and kink practices to explore the tension between danger and care in marginal spaces. But what struck me most in watching it was an overwhelming sense of loneliness. Without the context provided, I might have read the piece more as a meditation on artificial intimacy, suggesting a future in which connection is simulated, bodies are assembled, and touch is artificial. The absence of direct engagement with the audience, the sterile quality of the white mask, and the strange, tender attention given to these fabricated figures all deepen the sense that this is a space inhabited by White alone.

Design plays a crucial role in shaping the world of the piece. Props by Chris White and scenography by Steph Cyr help build a world that feels both sterile and fragile, like a lab or memory chamber. The black box is interrupted by a stark white curtain, and fragmented white paper is scattered across the floor. One sheet of paper is used to trace White’s body; others remain littered like remnants of something half-formed or forgotten.

Maria Kofman’s costume design, with all three figures in white masks, adds to the feeling of anonymity and duplication. White never removes his mask until the final bow, and even when he briefly takes it off to breathe, he turns away from the audience, preserving the strange, closed-off world of the piece.

only child is quiet, deliberate, and sparse in its movement—more focused on atmosphere and presence than on choreography in a traditional sense. It’s not an entry-level work. It asks a lot of the viewer in terms of attention and patience. But I really enjoyed it. Its stillness, design, and underlying tension held my focus throughout.

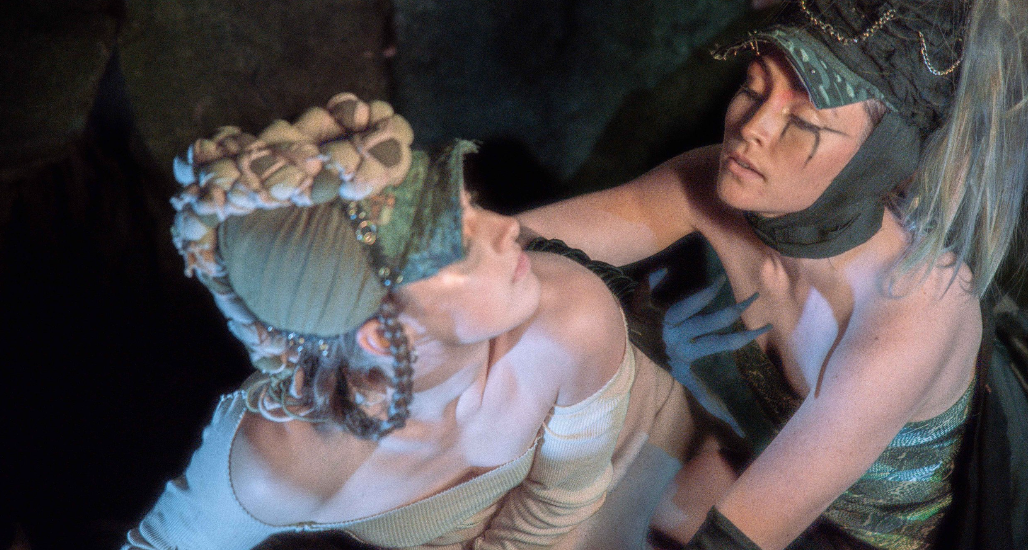

After a brief pause for a prop and set change, the theatre fills with smoke and the scent of incense, carried through the space by Cairns. We are then met with Sometimes the Sex is so Good, choreographed by Tavia Christina of Near & Far Projects and performed by Eleanor van Veen and Katie Adams-Gossage. Onstage: an old wooden desk, a chair, and a dog bowl filled with water from a small planter. It’s a minimal, almost domestic setup for what quickly unfolds into something charged and obscure.

The program text frames the work as a reflection on collapse and co-dependence: “How can we work through disaster together? Do we?” The tone is apocalyptic—queer, gritty, and strange. At one point, gobs of spit stretch from the performers’ mouths to the floor. The dancers simulate intimacy that teeters on the edge of violence, and their long, physical duets atop the desk are full of constant shifting and rocking.

The movement is jagged and taut, full of tension and torque. There are moments of choking, collapse, and almost-feral closeness. At times, it felt like the two performers were moving through some kind of ruin—of the body, the world, the self—and still choosing to stay. The experience was intense and unexpected, and likely not what a casual viewer would anticipate.

Angela Cabrera’s costumes feel dark and otherworldly, full of texture, fake hair, and odd puffed-out forms that make the dancers seem almost post-human. The original score by Luke Gruntz and Dæm combines white noise and broken sounds with eerie melodic stretches, creating a shimmering tension that mirrors the choreography.

I am not sure I fully grasped every symbolic gesture, and maybe that’s the point. It’s the kind of work that asks for patience, attention, and a willingness to sit with discomfort. But even in its ambiguity, I appreciated what it was reaching toward: something queer, chaotic, and unresolved, where intimacy can be both a comfort and a trap.

Together, only child and Sometimes the Sex is so Good offer very different but equally challenging visions of queer performance. As a double bill, Sweet Ephemera doesn’t offer easy takeaways or feel-good closure but asks us to sit with ambiguity, discomfort, and complexity. In a city full of rainbow spectacle, it felt good to spend an evening with work that leaned into the uncanny instead of smoothing it over.

Sweet Ephemera, presented by DanceWorks, is showing in the Studio Theatre at Young People’s Theatre (165 Front Street East, Toronto). It runs until June 26, 2025. For tickets, please click here.

Content Warnings: Violence, abuse, bodily fluids, intimacy, scents, loud sounds, bright lights, mature subject matter. Recommended for mature audiences 14+.

DanceWorks.ca

Facebook: DanceWorksToronto

Instagram: DanceWorksToronto

- Photos 1: Photo by Francesca Chudnoff, featuring performers Katie Adams-Gossage and Eleanor van Veen in Sometimes the Sex is so Good.

- Photo 2: Photo of Calder White in only child. Photo by Kaylee McCullough.

- Photo 3: Photo of Katie Adams-Gossage and Eleanor van Veen in Sometimes the Sex is so Good. Photo by Kaylee McCullough.

Written by Deanne Kearney

DeanneKearney.com @deannekearney

0 Comments Add a Comment?